Public and Private Keys, Part I

What "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" can teach us about risk: Quantum; One if by land, Two if by Sea; Regulators Mount Up

“Everyone may be ordinary, but they're not normal.”

― Haruki Murakami, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World

Risk Developments this letter:

Quantum

Regulators Mount Up

One if by Land, Two if by Sea

Risk Noir

In the early 1970’s a shadowy government organization clandestinely invented an encryption innovation that would change spying, banking, communicating and the world. Asymmetric encryption, first invented in secret in the early 1970’s and then discovered publicly in 1976, allows for two parties to exchange keys, free of context and in public. The advent of the World Wide Web in 1989 created a need for authentication and secure communications, an opportunity for asymmetric encryption to change how trust worked around the world.

Four years before the World Wide Web, and less than a decade after asymmetric encryption became public, Haruki Murakami published “Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World” a novel that is part cyber-thriller, and part investigation of identity through self and the other. Its odd structure allows it to be read as a dialectic between math and myth, data and dreams, society and self, or as I hope to do, here risk and uncertainty.

The book is split into alternating narratives. First is the Hard-Boild Wonderland, a noir cyberpunk world in which a mundane programmer (known as a calcutec) is pulled into a gritty underworld and offered a dangerous task. Second is the End of the World, an ethereal fantasy town in which the protagonist is assigned a role as dream interpreter and must face the challenge of losing his shadow. Murakami’s deep attachment to detective stories is found in nearly all of his works and “Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World” is one of the clearest examples. He often adopts pulp detective story techniques to investigate existential questions, most often, a man trying to find himself, but In “Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World” he is even more explicit.

The novel begins with the protagonist, a programmer (calcutec), descending into subterranean Tokyo. If you’ve ever worked a boring office job, but wished there was a hidden world of danger and excitement that could pull you in at any moment, this story is for you.

In the labyrinthine sewers, he meets a scientist, whose granddaughter enlisted the calcutec to encrypt secret experimental data. The calcutec works for The System, a corporate government in a constant battle to keep information secret from a criminal syndicate known as The Factory. After his apartment is trashed by thugs and the scientist’s lab is broken into, the calcutec finds out he has only 36 hours to live. The procedure that allows him to encrypt information using his subconscious has killed all the other calcutecs, and performing this task for the scientist has sealed his fate as well. Surprisingly, his reaction is nonplussed, and he spends the remainder of the time tracking down the scientist with the granddaughter, running errands, going on a date with a librarian and feeding birds in the park.

In the second narrative, our protagonist (unclear if they are related) arrives in a fantasy town. If you’ve ever doubted yourself or had to reinvent who you are after a breakup, the death of a close relation or a major life setback, this story is for you.

The protagonist is assigned the role of dream reader and becomes acquainted with the town, its inhabitants, geography and rules. The town is populated by non-player characters (automatons), including a gatekeeper, a librarian, a colonel and the caretaker. This strange town also has two types of inhabitants that retain their minds, the dream reader’s shadow and a herd of unicorns. The main action in this narrative revolves around the impending death of his shadow, who has been cut off from him, and the decision of whether the dream reader should try to escape with his shadow or embrace his fate.

The duality of the stories pose questions about risk and uncertainty, while each individual story also touches on encryption, identity and self. To understand how risk is distinct from uncertainty we will explore the relationship between the stories.

My favorite definition of risk, stated on The Refractor before, is Peter Bernstein’s “more things can happen than will.” Risk deals with the concrete and finite. In the whole known universe of things that can happen, each happening has a probability of occurring which can be measured.

Uncertainty exists beyond the known. Economist Frank Knight described the concept thus, “a measurable uncertainty, or 'risk' proper, as we shall use the term, is so far different from an unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all." That is, measurable uncertainty is simply risk, and true uncertainty is that which cannot be measured.

Below is a matrix, sometimes called Rumsfeld’s Matrix of Epistemic Uncertainty (parenthetical are mine) that is useful for understanding risk versus uncertainty.

The Hard-Boiled Wonderland is in green, it is a world of risk. Mathematical determinism, bodily drives, running errands, even science exists in a world of knowable probabilities. The End of the World is in red, it is a world of uncertainty. Dreams, absence of desire, inherent tasks, even the self exists beyond the world of knowable probabilities.

Returning to Murakami’s “Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World,” equipped with this knowledge, it is easier to understand the End of the World as “uncertainty world” and Wonderland as “risk world.” Risk world is a place of measurable quantities, hypotheses, physical needs, consequences, cause and effect.

In this world calcutecs perform two functions with data they are given, laundering and shuffling. Murakami does not not exactly provide a technical description of encryption, but it is reminiscent of the two types of encryption commonly used, symmetric key and asymmetric key encryption. Laundering is described as:

“I input the data-as-given into my right brain, then after converting it via a totally unrelated sign-pattern, I transfer it to my left brain, which I then output as completely recoded numbers and type up on paper. This is what is called laundering. Grossly simplified, of course. The conversion code varies with the Calcutec. This code differs entirely from a random number table in its being diagrammatic. In other words, the way in which the right brain and left brain are split (which, needless to say, is a convenient fiction; left and right are never actually divided) holds the key.”

The other function, shuffling, is a top secret and dangerous procedure described as:

“Then they instructed me on how to shuffle: Do it alone, preferably at night, on neither a full nor empty stomach. Listen to three repetitions of a sound-cue pattern, which calls up the End of the World and plunges consciousness into a sea of chaos. Therein, shuffle the numerical data.

When the shuffling was done, the End of the World call would abort automatically and my consciousness would exit from chaos. I would have no memory of anything.

Reverse shuffling was the literal reverse of this process. For reverse shuffling, I was to listen to a reverse-shuffling sound-cue pattern. This mechanism was programmed into me. An unconscious tunnel, as it were, input right through the middle of my brain. Nothing more or less.

Understandably, whenever I shuffle, I am rendered utterly defenseless and subject to mood swings.

With laundering, it's different. Laundering is a pain, but I myself can take pride in doing it. All sorts of abilities are brought into the equation. Whereas shuffling is nothing I can pride myself on. I am merely a vessel to be used. My consciousness is borrowed and something is processed while I'm unaware. I hardly feel I can be called a Calcutec when it comes to shuffling. Nor, of course, do I have any say in choice of calc-scheme.”

To understand encryption in the real world you need to know three concepts: one-way functions, ciphers and keys. You likely have an intuitive sense of symmetric encryption which just requires a key and a cipher.

The cipher is the algorithm for transforming characters or strings of characters from plain text (that is readable) to cipher text (unreadable). You can think of it as similar to a codebook or a mapping of characters and strings to various symbols (of the same language or not). This is called a one-time pad or as Murakami says a “number table.” In practice a cipher is a series of operations and devices, such as substitution and transposition, used to transform characters.

A key is what makes each transformation unique. This is the “seed,” or if you’re thinking of the one-time pad, it is how you would set the relationship between plain and cipher texts. With just a key and cipher, you too can launder like a calcutec! Unfortunately, for both parties to read and encrypt text they must share a key, or know the split of calcutech’s brain. This makes it impractical for establishing a shared secret without having a previous shared secret.

This works because of one-way functions. These are mathematical relationships that are easy to perform given the inputs, but difficult to reverse given the outputs. Think of how a pad lock is easy to lock, but difficult to open without a key. Asymmetric encryption, sometimes called public-key cryptography, can be described as mixing paints or sending mail with a lock.

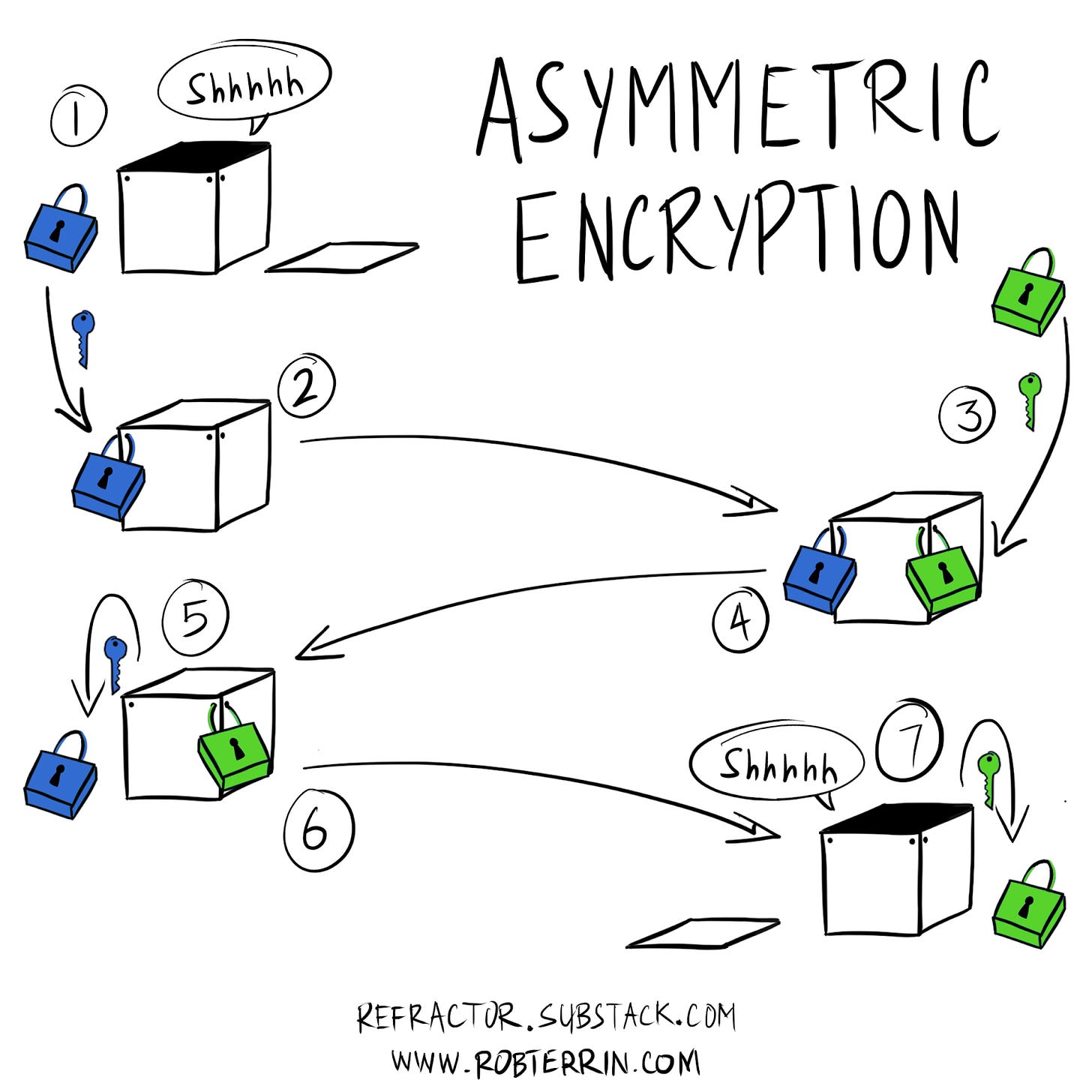

Imagine you need to send a secret to a friend through the mail.

You purchase a padlock and lock your secret in a container, while keeping the key in your possession

Then you send the locked container through the mail, knowing you hold the only key

Your friend receives the locked container and locks their own padlock on the container, keeping the key to their padlock in their possession

Then they send it back to you

You unlock your lock, confident that the container will remain locked with their lock in transit

Then you send it back one last time

Finally, they unlock their lock that can only be opened by their key

Ok, so what does all of this have to do with Murukami, identity, risk and uncertainty? Digital signature. What? That’s right, digital signature is the cornerstone. Public key cryptography allows for authentication and integrity of a message. If you are familiar with block chain or cryptocurrency you may have come across Merkle Trees, a form of digital signature. If not, don’t worry, it’s analogous to a form of the asymmetric encryption described above.

Think of it like this, if your friend just wanted assurance that it was you, and only you, that was sending a message, they could ask you to send your unlocked padlock to them. They could lock it and send it back. Then you could unlock it and send it back to them.

Murakami’s sea of chaos in the protagonist’s shuffling is the private key. It is the subconscious; the self; the uncertainty in a world of determinism. Encryption is probabilistic, self is not. The calcutec’s identity is the key that opens and locks the door between worlds.

Losing one’s identity is dangerous, just as losing your private key can be. Murkami’s fundamental insight is that finding yourself can be just as fraught. To learn why, stay tuned for next week’s Part II on identity and self.

Tell Me What You Think!

A short interlued before we get to the risk developments. If you like what you’ve just read, I’d love to send you part II next week. please subscribe here:

If you really love what you just read, please share The Refractor with your friends. I’m a one-man band, reading news and litearture, writing criticism and analysis, drawing and publishing, so any votes of confidence go a long way:

If you hate it, please let me know what you didn’t like or what you think I got wrong. You can leave a comment here, email me at robert.terrin@tailrisk.com or find me on twitter @robterrin. Your candor is more important to me than flattery:

OK, thank you for bearing with me. Finally let’s get on to the risky business.

Quantum

Quantum computing is a topic that represents different threats and opportunities to different groups, making sometimes strange bedfellows. Most of the QC innovation is happening in big tech firms, startups, research scientists and the military-industrial complex. At the same time preemptive quantum safe encryption is being developed by finance, crypto currency supporters, the intelligence community and privacy advocates. You don’t often see bitcoiners and ibankers, hyper-scale and hyper-growth, SigInt and NGO’s coupling up, but here we are.

Visa and JPMorgan announced new research they are publishing in quantum safe encryption theory. If they are successful in applying this theory, it will likely help their cryptocurrency detractors. At the same time, the NSA is putting out guidance for quantum safe crypto.

Honeywell, the large industrial and defense manufacturer, announced a 10 qubit computer. Not quite the 72 qubits of Google, but they claim an impressive enough “quantum volume” to leap ahead of IBM who are shooting for an 1000 qubit computer by 2023.

It’s an arms race with global consequences unheard of since the nuclear arms race of the Cold War, and just like the Cold War, it is reshaping alliances, forcing groups to take sides and ratcheting up tensions, only this time the players aren’t just nation states.

One if by land, Two if by Sea

One pet theory I’ve held privately for a while is that the only way for financial innovation to come to the U.S. is invasion, by a challenger who can break the lobbying fortress American incumbents have constructed. Overcoming the parapets and ramparts of independent community banks and large investment banks will take an outsider with the resources and firepower to lay siege.

That outsider could arrive over land with allies from the north like the recent TikTok/Shopify collaboration. It could come, like the redcoats, across the seas as Revolut and Monzo are doing. Maybe, like the first Europeans to set foot in the New World, it will come from Scandinavia, in the form of Klarna. Or Maybe it will come up from Latin America through Mexico like Santa Anna, Fitbank and someday NuBank could pose serious challenges.

One reason outsiders have such an advantage is the lack of transparency and options for American banking back ends. With over 70% of core software market share going to the top three providers (Fiserv, Jack Henry and FIS). The rest of the market is highly fragmented and many banks have cobbled together their own systems with the help of systems integrators and consultants.

The U.K., where just three banks own half the market, leads the world in terms of open banking standards. The three big players are so dominant that they aren’t threatened by open standards, so it is no surprise that it has generated a number of challenger banks. Smaller countries or countries with more recently developed financial systems have fewer legacy systems and less competition to contend with.

The U.S. by contrast has many more players of all sizes. In some ways the U.S. has the most competitive banking system with the greatest choice, it’s just that under the hood, they’re all the same. What appears to be a free and dynamic market full of uncertainty has settled into complacency and unimaginative risk management. This has made us a laggard in open banking, but pressure from merchants and challengers is forcing a change. Opening up to competition may be unsettling, but it’s time for American finance to find a new identity or face the other.

Regulators, Mount Up

In regulatory news abroad, the mega fintech firm Ant Group suspended it’s IPO. Yahoo calls it an identity crisis. Byrne Hobart at The Diff is calls it a fitful convergence. I call it Knightian uncertainty. China has never had to address the cognitive dissonance between a centrally planned economy, capital controls and property rights so publicly before.

China has cracked down on property rights when it affects capital flows like secret real estate deals and crypto currency, but that at least has a veneer of respectability. Cracking down on payments, as they did when Ant split form Alibaba had to be done quietly, and resulted in Alibaba shareholders clawing back 33% of Ant. Given that Alibaba has large foreign investors such as SoftBank, Altaba (f.k.a. Yahoo), Blackrock and other institutional foreign investors, the added pressure for more Western governance is immense, but the untested Chinese regulatory system is a risk to its banking sector that the Community Party could not stand.

If you feel a bit like I’m casting stones here, don’t worry. We in the West live in our own regulatory glass house. After the much lauded Plaid acquisition by Visa was announced and the fanfare died down, regulators are raising antitrust questions. It’s hard for me to see Plaid turning into a real payments challenger to Visa, but also hard for me to see where the consumer benefit in the acquisition lies, but whichever argument wins out, the possible outcomes are defined. American fintech lives firmly in risk world, but as the American crisis of conscience continues to unfold, that may not hold.

Gratitude

Big thank you to Snigdha Roy and Nichanan Kesonpat for wonderful comments. As usual, Roger Farley, Tom White, Sachin Maini, Vinit Shah and Reza Saeedi your workshop feedback was inspiring and educating. Thanks Dan Stern, Tarikh Korula, Brittany Laughlin, and Chris Sparks for your interest and support! Finally, Byrne Hobart, Todd Baker, Mike Solana, and Dan Geer for sharing ideas that one way or another helped me write this piece.