Agency Risk

What Power House can teach us about risk: Paradigm Grift, Ok… fine... Archegos, Cyber Impact, Defensive Talent, Brinkmanship

The only way I’m going to be wealthy is if I take a risk. And if I take a risk now, I’m falling five foot, eight and a half inches. If I take a risk two years from now, I’ll have a bigger mortgage, I’ll have a lot more cash that I’m leaving on the table, and I don’t know if I have the stomach to do that.”

- David Greenblatt (founder of Endeavor), Power House: The Untold Story of Hollywood’s Creative Artists Agency

Risk Developments this letter:

Paradigm Grift

Ok… fine... Archegos

Cyber Impact

Defensive Talent

Brinkmanship

Dealers, Brokers and Agents

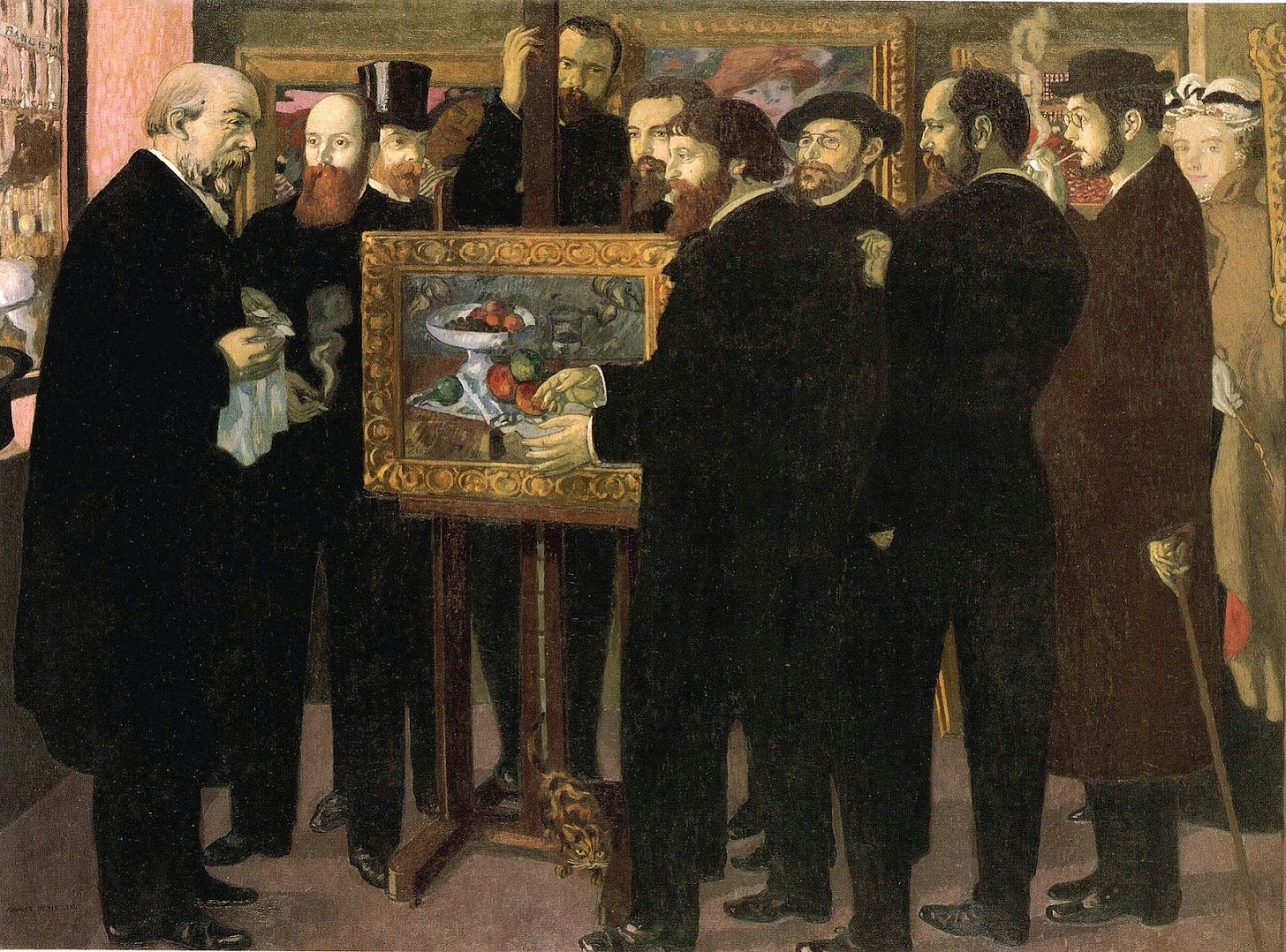

When legendary founders Ben Horowitz and Marc Andreesen set up the now hugely successful venture capital firm, Andreesen Horowitz (A16Z), did they model it after previously legendary VC’s like Sequoia, Kleiner Perkins or Accel? No, they modeled it after the talent agency Creative Artists Agency (CAA). The CAA story is fortunately recounted in dialogue by the book “Power House: The Untold Story of Hollywood’s Creative Artists Agency.”

As former founders themselves, Marc and Ben observed that the shift in power that occurred in the movie business in the 1970’s, from major production companies to talent, was occurring in startups as well. They correctly identified that the scarce resource in new ventures was no longer institutional know-how or capital, but talent. Unlike previous eras of venture such as whaling (someday I’ll write a Moby Dick post) or silicon semiconductors (Fairchild Camera Instrument), the best way to manage risk in new ventures today was to direct clusters of talent.

Risk management in asymmetric worlds such as venture, security, movies or catastrophe insurance is fundamentally about achieving or avoiding extreme outcomes. Because outcomes are always overdetermined, it is important to zero in on the commonalities between all extreme outcomes in a field. All successful movies have a star or make someone a star. All natural disasters happen in an area where there is a vulnerable population (otherwise they are called adverse events). All security breaches require the exploitation of a vulnerability (human or machine). All great venture investments have an exceptional team.

When a particular resource is scarce, market makers, brokers, agents and dealers can be invaluable. To quickly differentiate between these liquidity providers, think of market makers and brokers as working for the deal, agents as working for a specific party and dealers as working for themselves. What Andreesen and Horowitz recognized is that venture is a people business, and whoever would be able to arrange the right cast of characters, would get a share in the economics of the biggest successes. What they did better than CAA was to act as a dealer, not just a broker.

Still some of their deepest lessons come from CAA, and can be discovered in “Power House.” CAA was founded by Mike Ovitz (interviewed by Marc Andreessen here) and Ron Meyer. Mike is legendary as a salesman, known for his hustle and for being a typical flashy Hollywood agent. Ron is the veteran son of immigrants and known for his work ethic, deep sense of commitment and enduring loyalty. This team of ambition and flair coupled with duty and grit was a winning combination.

First is the importance of originality. CAA was a scrapy firm started by traitors of the William Morris Agency (WMA). WMA, which began representing vaudeville stars in 1898, is still one of the most powerful talent agencies in the world. When CAA was started, in 1975, they didn’t have the luxury of going head to head with WMA, so they picked off lower hanging fruit in publishing, directing, television and even professional sports. With fresh sources of scripts, vision and acting talent, they could offer formidable, and untapped, resources to movie production studios. Tapping previously uncontrolled resources in music, T.V., writing and sports not only provided alternative sources of revenue, but allowed them to offer a broader range of reinforcing services.

The second is the power of the package. CAA discovered early that if they brought various talents together, they could command a greater share of the economics. Instead of collecting 10% as a fee from each artist they represented, they could collect 5% of half the profits and 15% of the gross, if they bundled directors, writers and actors. This practice is lucrative, although controversial (The Wire’s David Simon has a famous amazing rant about it here). Not only did they make more money, but they could get projects done that production studios, previously blocked. This made their talent more loyal and happier, because creative talent is highly motivated by artistic vision. It also had the side effect of actually increasing box office hits, because, as it turned out, studios were not good at determining success ex ante.

The third, is how the firm itself was organized. Henry Kravis, private equity billionaire and founder of KKR, has routinely cited his dissatisfaction with the culture at Bear Stearns as primary motivation for founding a new company:

… I started with a specific culture in mind, which is one of the reasons we all left Bear Stearns. Bear was very much an eat-what-you-kill culture, and that’s exactly what we didn’t want. We were big believers in working together. We wanted everyone to share in everything we did, whether you worked on a deal or not.

Similarly, Ovitz, Meyer and the rest of the founding team were dissatisfied with the office politics of WMA, and sought to build a partnership. This reinforced their originality and ability to package deals. With nobody fighting over deal economics, everybody would be happy to contribute their relationships to a package. In addition, the partnership allowed for a much broader set of services, including offering everything from financing to intellectual property. Legendary director Ron Howard had this to say about CAA:

The studio system is shrinking, but there are so many other ways to get projects going at an agency like CAA. They have relationships with financiers, companies, and distributors. It’s about trying to find that intersection point between what their client base, their talent, has to offer and what the marketplace will bear. I think they do it well, and I think they continue to do that thing that I care about the most, which is to allow a person like me to be able to connect with talented artists I want to work with. (10075)

Ultimately the founders of CAA had a falling out and the unique leadership team that built their culture fell apart, but a the next generation picked up the reigns and made it one of the premier sports agencies, expanding their crossover reach again, and even more recently their foray into politics (signing Joe Biden in 2017), seems to have paid off. In terms of equity ownership, private equity firms like TPG, Silver Lake and even Softbank have gotten involved in talent agency buyouts, seeing just how lucrative the business has become.

Returning to A16Z, we can see how the venture capital game, now shifted towards talent, changed, but what of other asymmetric games? Anytime risk and opportunity resides in the tails, brokers can create a bundle that is greater than the sum of its parts, and with payoffs and losses so unevenly distributed getting even a small percent of a massive outcome by controlling the scarce resource can turn and industry upside down.

So what of the security and risk space, specifically? We talk a fair amount about insurance brokerages, cyber talent, arms dealers and financial market makers around here. In one way or another, these are all either brokers, agents and/or dealers. Since security is the inverse of opportunity, the challenge is not to find the scarce resource that drives the economics, like venture, but to prevent a single point of failure from creating catastrophic losses. The equivalent here is knowing where the vulnerabilities are, whether that’s a zero day in cybersecurity, an excessively leveraged counterparty in finance or a hazard that amplifies the loss caused by a peril. When your job is to pick up pennies in front of a steamroller, the game is to stay alive, which is easier said than done.

Risk Developments

Paradigm Grift

One thing venture capitalists love talking about is a paradigm shift. The phrase was stolen from Thomas Kuhn’s “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” and is apt for describing emerging trends, although it was first coined to describe when a scientific idea or theory breaks the prevailing worldview among scientists. VC’s understand that the success of their investments is subject to many factors outside of their control, not least of which are technological or social trends. MySpace was Facebook before Facebook. Palm invented the first mass consumer handheld electronic device years before the iPhone. And so on.

Since the advent of cloud computing and mobile devices, there hasn’t been much to bet on. Driverless cars are taking longer than expected, AI has largely meant slight improvements to existing models and cryptocurrency, although presenting amazing speculative opportunities has not built a whole ecosystem of technologies on the blockchain, yet.

With the pandemic speeding along regulatory approvals in pharmaceuticals, there seems to be an opening. What else could be next? Apple, Facebook and Niantic are betting on augmented reality glasses. Microsoft is exploring liquid coolant baths for servers. IBM says its ready to deliver homomorphic encryption. Could this be the beginning of the next paradigm shift, and if it is driven by big business, are we moving away from a world in which talent is the main driver of startups? If not, maybe there trends are not as obvious as those listed above.

Ok… fine... Archegos

So I guess I have to talk about Bill Hwang’s Archegos blowup that is costing Credit Suisse $4.7B. Counterparty risk is always difficult, and with incentives to keep driving lucrative fees from hedge fund clients, risk management is not usually in a position to step in and potentially spoil a relationship.

There’s somet talk in my circles of the possibility that Hwang, happy with his record breaking year, took half his gains (about $5 billion) off the table into his personal account, and dared his prime brokers to raise his margin requirements. This is all speculation, but whatever the case, it’s more difficult to encourage cooperation and prudent risk management for a joint stock company, as opposed to a partnership, where all the upside would be shared equally. Maybe the chief risk officer did her job, and maybe she didn’t, but having somebody to scapegoat is pretty convenient so that gains can be captured by a few and losses fall on someone else.

Cyber Impact

Speaking of losses. CNA’s website is back up after at two week outage due to a ransomware attack. One theory is that the website was down for a long time because they were following correct procedure and ensuring the ransomware didn’t spread. In a bit of good news, their email systems were fully recovered within one week. Corporate insurance brokers don’t sell a lot of policies without picking up the phone, so the website is less like Amazon and more like the DMV. In some ways this makes insurance brokers better suited to a high cyber risk world.

The New York isn’t letting insurers off the hook however. Following the Department of Financial Services’ framework and recent enforcement actions, the state legislature is considering tougher privacy regulations and higher standards for businesses. So far the regulation has fallen most heavily on the financial services industry, with insurance being of particular interest. What could be more interesting is to encourage creative bundles that bring together talent, capital and know-how that addresses the problem from new angles.

Defensive Talent

One area in which talent is scare, but has a hard time commanding a share of the economics is defense. In part its because the players are so big and because the institutional know-how is so difficult to navigate. Raytheon isn’t slowing down it’s D.C. area recruiting. One interesting feature of cybersecurity, as opposed to most defense technology is that although it isn’t revenue generating, it also isn’t easily off-shored.

Boeing, for example, has all of its manufacturing plants in the United States, and then flown to the customer. In one recent $1.6B order the U.S. and Australian Navies are buying 11 P-8A (military grade 737’s) equipped with sonobuoys, essentially submarine hunting radar devices attached to buoys that can be deployed by plane across a wide area, perfect for monitoring Chinese submarines in the South China Sea.

Brinkmanship

Since the end of the Cold War, there hasn’t been much threat of great power conflict. The U.S. has, of course, faced enemies, but enemies it was sure it could defeat and who were also sure they could be defeated, at least temporarily. Now that history is rebooting two main points of friction raise troubling signs. The first is Taiwan, which Scholar Stage has a nice writeup on. The political, geostrategic and economic importance of Taiwan make this by far the biggest concern in the world today.

There is, however another threat to keep an eye on. Russia is moving materiel to Crimea in an apparent build up and simultaneously strengthening its arctic forces. Putin’s opportunism probably indicates he’s not so much plotting a second (third?) Russian Empire, but looking to put together original sets of talent, capital and know-how to take advantage of asymmetric risks, while the U.S. is distracted with China.

This new era of international affairs is going to require innovation and new models of procurement, intelligence, warfare, diplomacy and peace making. It’s time to rip up the old playbooks and embrace the

Gratitude

Big thanks to Tanner Greer, Christopher Ming and James Andrew Miller for your writings which all found their way into and inspired this piece.